Servicing a 1971 Seiko Lord Marvel 5740-8000

An Owen Berger inspired venture.

I read about Mr. Owen Berger in Tony Traina’s newsletter ‘Unpolished’. Impressed, I went on a deep dive to learn about what he’s been up to. He has seen work from the legendary likes of Eric Wind and Jeff Stein, has had a watch on the Met Gala red carpet, and operates under the Instagram handle @whitewhalewatches, but all of that was pretty easily uncovered information. I wanted to know what drives him to learn and progress.

I myself have recently been seeking the mentorship of a ‘sho-nuff’ watchmaker to really look over my work, and after a conversation with a recent graduate of Lititz who has graciously agreed to help with my quest, an interesting observation was made that stuck with me. He asked why I wanted to pursue watchmaking. Was it for the practice of the craft? Or for the end result of a well serviced watch? He argued that because those two aims are quite different, they should net different goals. We talked for over an hour about it, humming and hawing over how much, or little, of each we felt. I settled on a bit of both driving my personal pursuits, but I was interested in applying that thought pattern while researching others that I look up to, Mr. Berger included.

Having begun my watchmaking journey in my twenties, it’s incredibly inspiring to see Owen do it in his teens, and at the level that he is already operating. In my search for how he found the art and came to be on Tony’s newsletter, I came across a 2024 NAWCC article transcribing an interview and some of his escapades in watchmaking. He mentioned in this conversation that he at the time was daily driving a hi-beat Seiko Lord Marvel, and that was enough reason for me to begin my hunt. If it strikes Owen’s fancy, I’d argue there’s something there that should be respected by other up and coming watchmakers. Envious but reverent of Owen and his early start in the craft, and eager to continue my own climb toward competency, I resolved to procure a hi-beat Seiko Lord Marvel myself to try and see why one of my favorite watchmakers right now wore one every day.

Before I start down the road of the Lord Marvel, a quick aside to cover my watchmaking escapades since my last post:

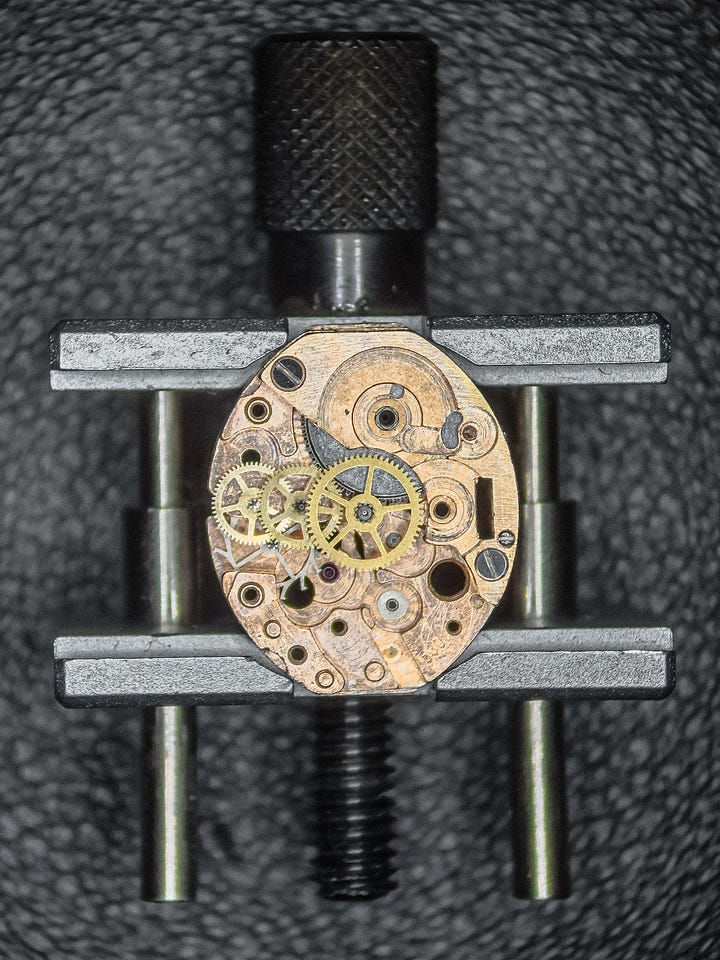

A tank-style Camy with an incredibly comfy bracelet holding an ETA 2369 and a painted-over dial that I snagged at a local auction and serviced for a friend who shares a logo with this dial. And a pretty sweet white gold plated Tissot Saphir holding a TS 530 that I snagged for my wife while thrifting on a visit to Portland, OR.

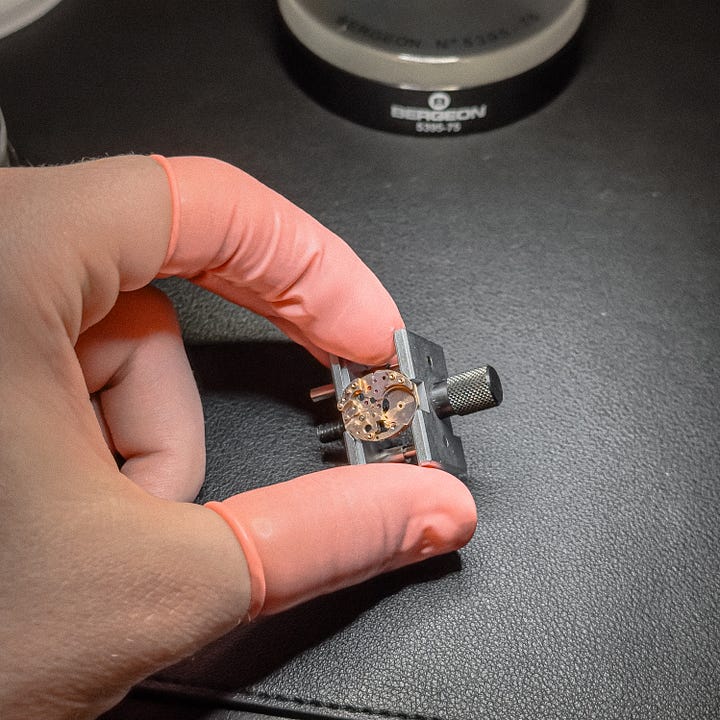

Tiny parts all around! Some details and scale references of the pre-service TS 530.

On to the main event. After some looking back, the newsletter that introduced me to Owen was released on August 23rd, and my inquiry about this watch to its seller happened the same day. I didn’t do a very good job of following Tony’s rule #42, but then again those rules weren’t publicly set until late September. I felt like I had a great reason to look, and a very solid price showed its face considering condition. To be completely honest, like a ton of the watches from the Suwa/Daini duel era, I’d looked at the 5740-8000 before. Owen’s interest just gave me enough reason internally to pull the trigger and see for myself what made it a watchmaker’s watch. Because of my previous interest, this one that had been filed away in my Reddit profile’s ‘Saved’ tab quickly made its way onto my bench.

I was (very thankfully) able to snag it from outside of the US just before the ‘de minimus’ exemption disappeared. It doesn’t show perfectly, it’s obviously been well loved. The crown isn’t original (which I’m now post-service in the process of correcting) and the dial has some wear around 12 and between 6 and 9. Being a bit of an impulse purchase though, and one that I was treating as a case study more than anything, I felt good about the price. It was also running, which meant that I could hopefully dig into a service without a bunch of fuss.

The lines aren’t so soft that the case looks like an amorphous blob. I wouldn’t call anything ‘sharp’, but I would still use ‘decently defined’.

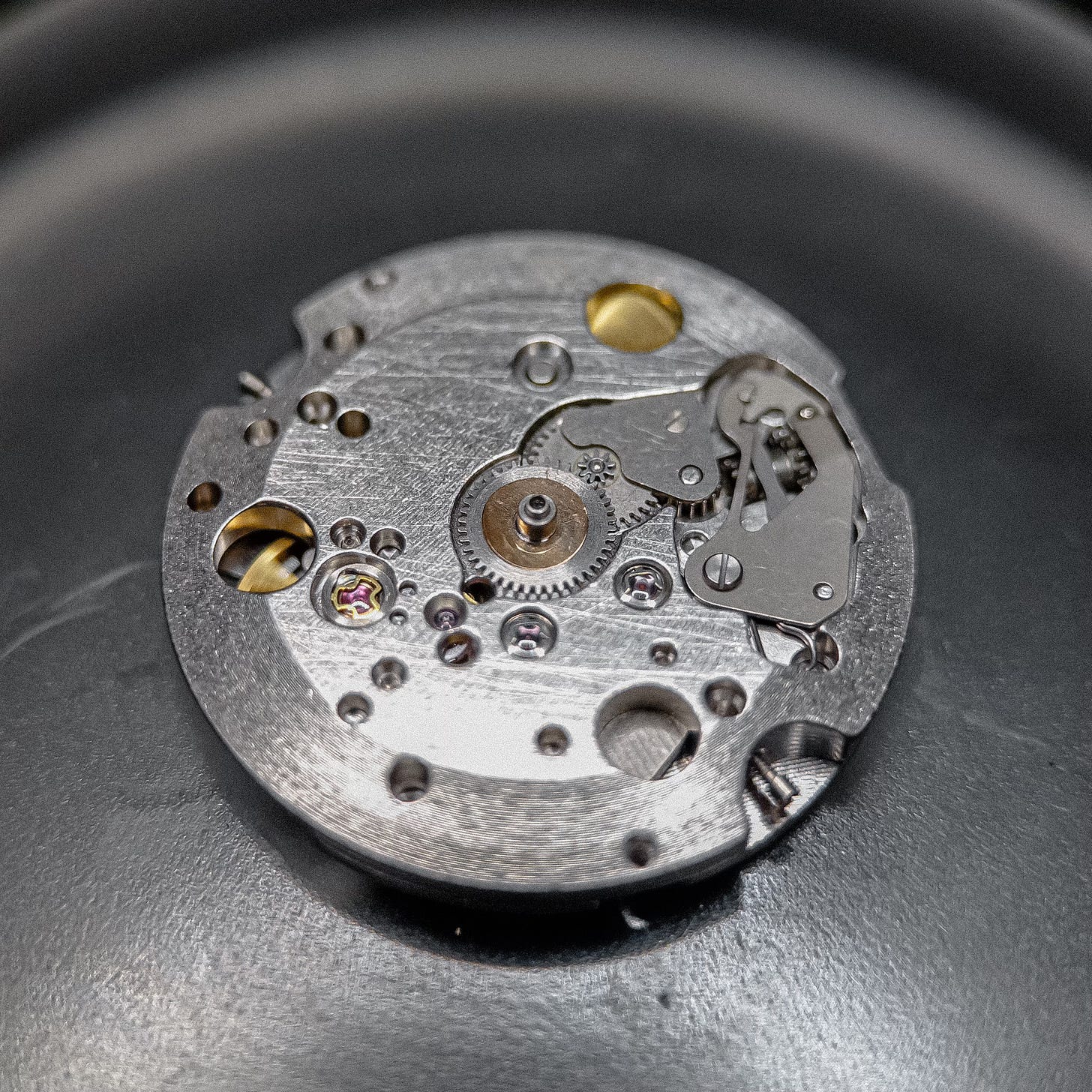

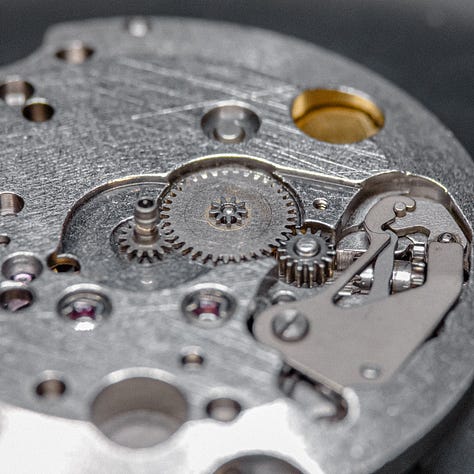

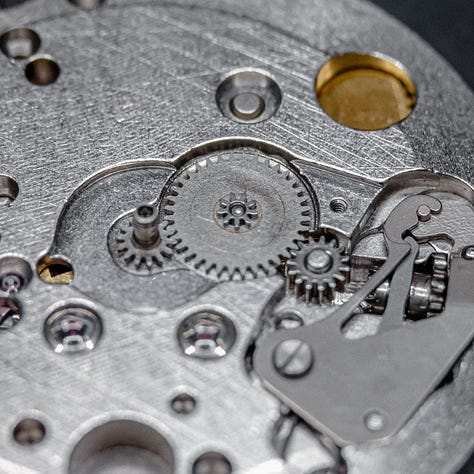

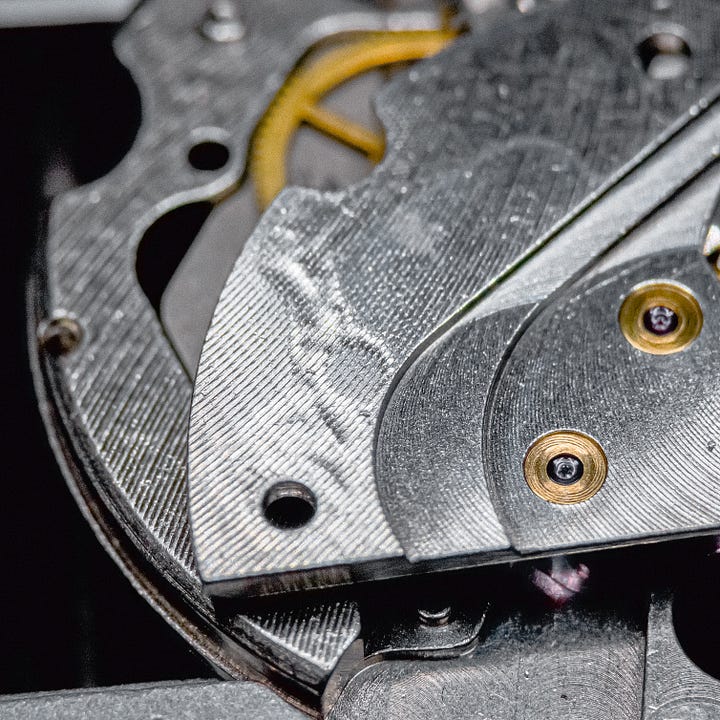

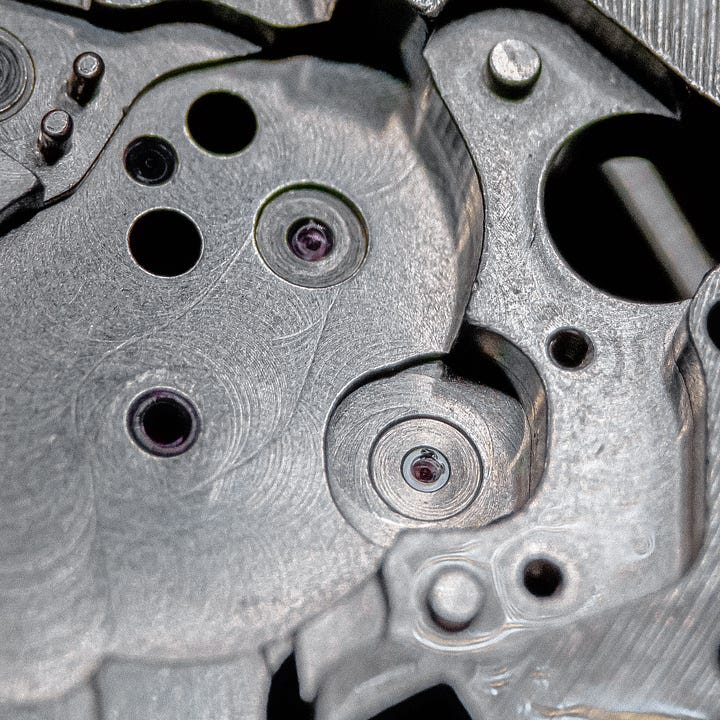

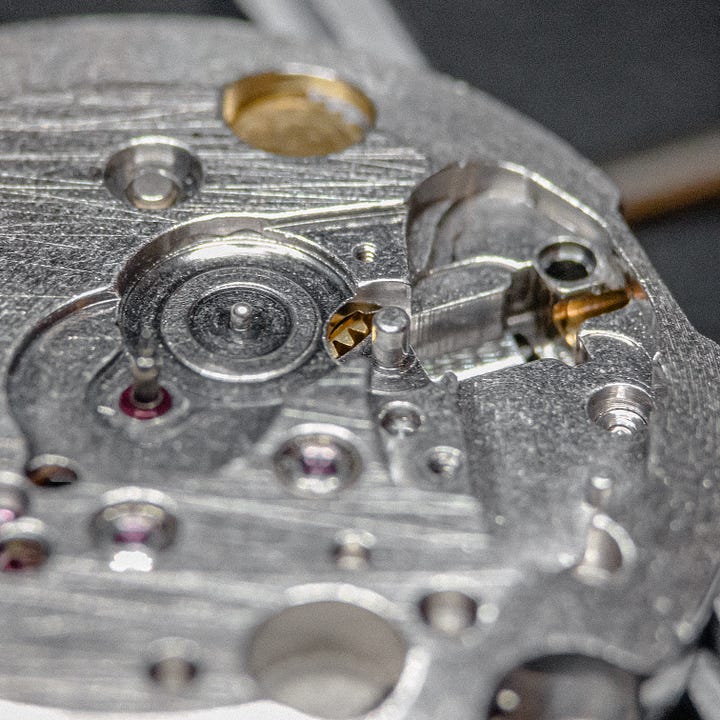

This is my eleventh service, my fourth Seiko, but the first time I have allowed myself to work on a watch (relatively) nice enough that I opened up the caseback and felt like I was looking at something completely different. Even is it’s pre-cleaned state, the construction and level of finish on this 5740C was certainly at a more sophisticated level than what I had come into contact with in my 6106s, 6619s, 7005s, etc. Everything seemed intentional. No afterthought screws holding a feature in place that was obviously added on, no disregarded angles or tolerances, no mixed finishing across bridges, it’s definitely still utilitarian, but elevated. The industry talks about finishing like it’s God’s gift to man, and I’m not saying I have the experience to preach whether it is or not, but this movement left me surprised at how big an impact a little effort in that department can have on the eyes.

I’m not trying to make this to something it’s not. I understand we’re still looking at a mass-produced Seiko movement, and I didn’t kid myself into thinking it anything more than that. I did begin however at this moment to realize that this was surely some of what Owen felt that led him to praise this watch.

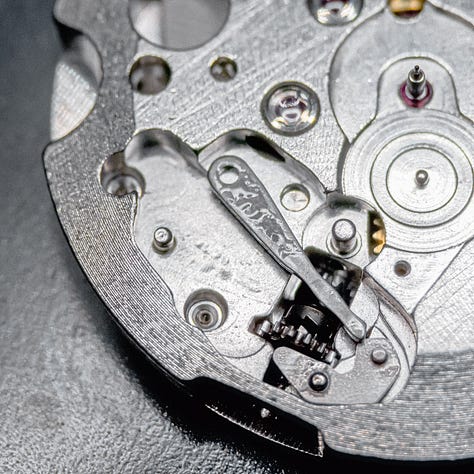

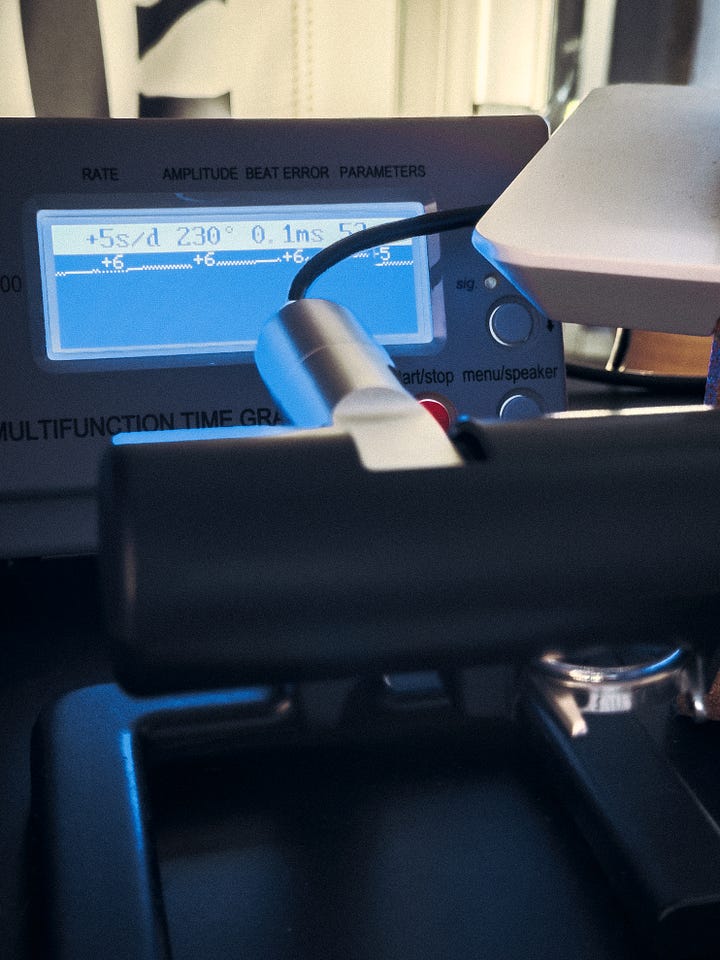

Initial measurements suggest that it’s been a minute since a service has been issued. Thankfully the hairspring stud is on a moveable arm that will allow for beat error regulation, and our regulation pins are situated with micro-adjust capabilities, so as long as we can ensure a sizable improvement in amplitude with our service we should be in good shape.

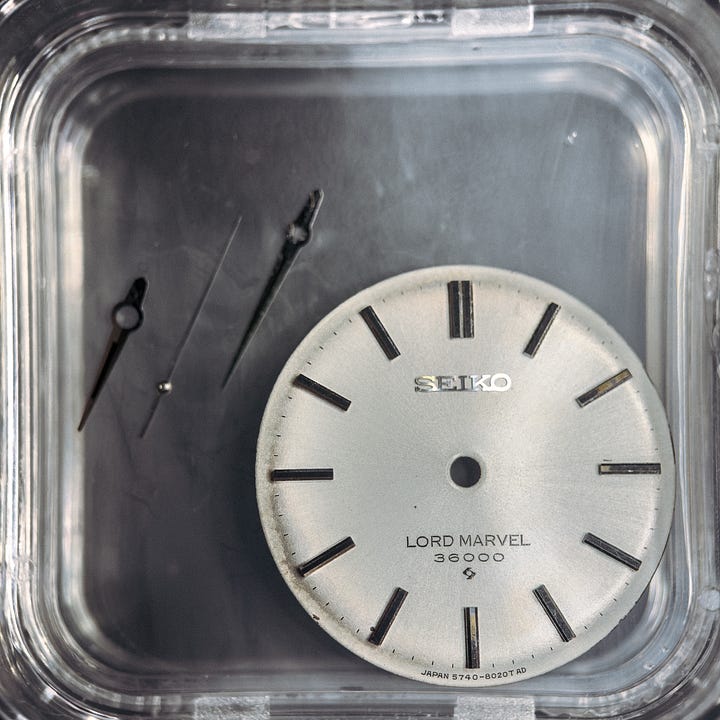

Stem removed and everything out of the case, time to take a peek at the bare dial. A couple of worn areas previously noted, and a few small dings throughout but nothing unwearable. The hands and dial removed and set away, the movement headed to a holder, it’s time to disassemble the case.

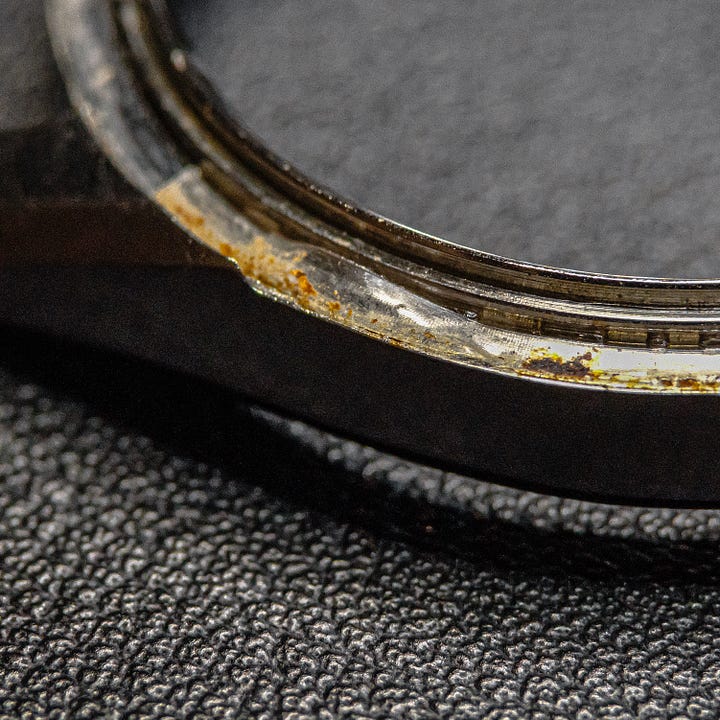

This is where things get unfortunately interesting. As I finagled the bezel and crystal off of the case by my usual means, I encountered some resistance and some horrible noises. I eventually decide to apply some force to aid in their removal and find that a previous ‘service’ had resulted in someone attaching the crystal and bezel to the case with some sort of adhesive.

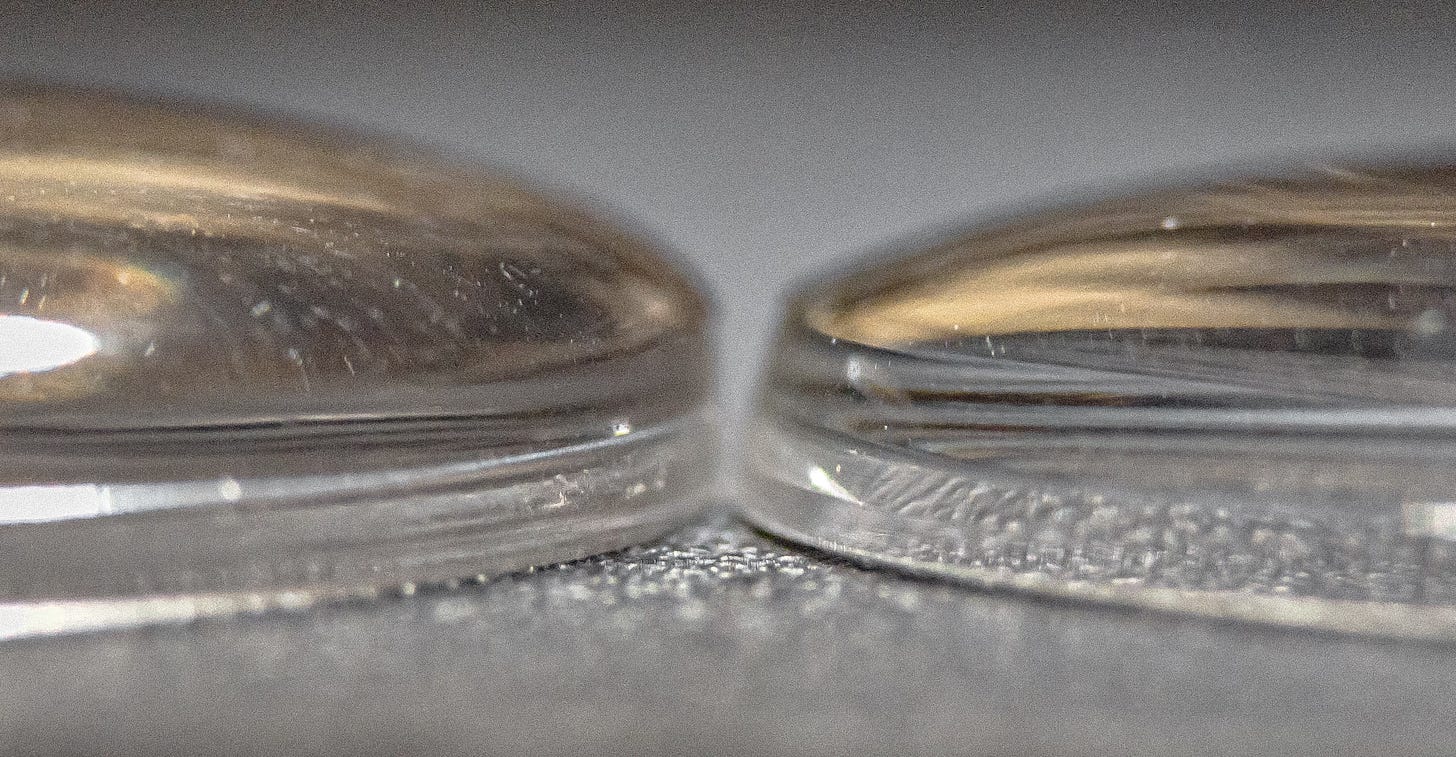

The cause of the glue job can be found here. The crystal that I pulled off of the watch (left) had a vertical wall that didn’t reach to allow interaction with the bezel, and the internal diameter of the crystal was too wide to interact with it’s seat on the case. This means that the bezel moved freely around the crystal, and provided no aid in holding it in place. This worried me, I wondered if the bezel for the watch had been replaced with an incorrect example, or had been modified to fit a different crystal at some point. After some comparison with photos of correct examples I became fairly confident that wasn’t the case, so I sourced a new OEM crystal photographed here (right) next to the original.

With this side-by-side view you can pretty clearly see why the last watchsmith to work on the crystal was forced to resort to adhesive for the example they’d sourced. The correct crystal has an angled wall that uniquely allows for the interior of the crystal wall to interact with its seat on the case and the exterior wall to interact with the bezel.

I spent far longer than I’d planned having to pre-clean with a dental pick and some peg wood to remove the tacky and dried adhesive from both the case and bezel. Having done what I could with manual cleaning methods I performed a preliminary test fit with the new OEM crystal. The tension of the bezel around it gave me enough hope that it’d fit properly after a good cleaning to continue on.

Our first good look at the dial side of the movement. Everything looks to be in order, save for signs of major over-lubrication by the last watchmaker. I realize at least some of the amplitude issues may stem from the presence of so much lubrication on a sensitive hi-beat movement.

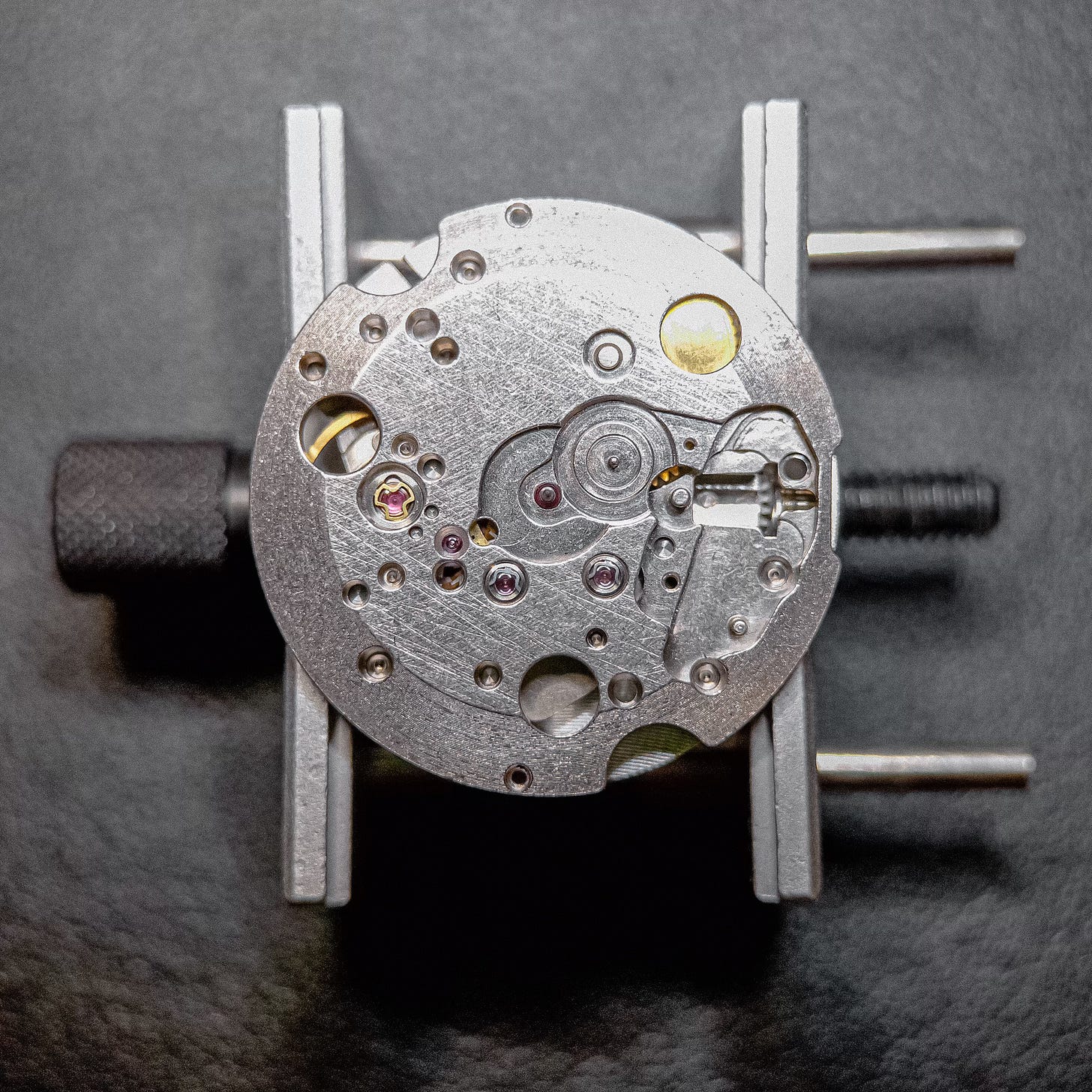

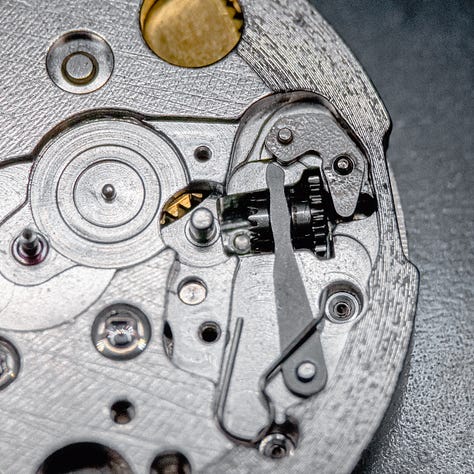

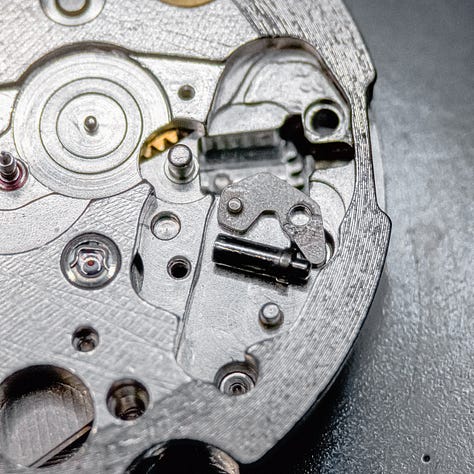

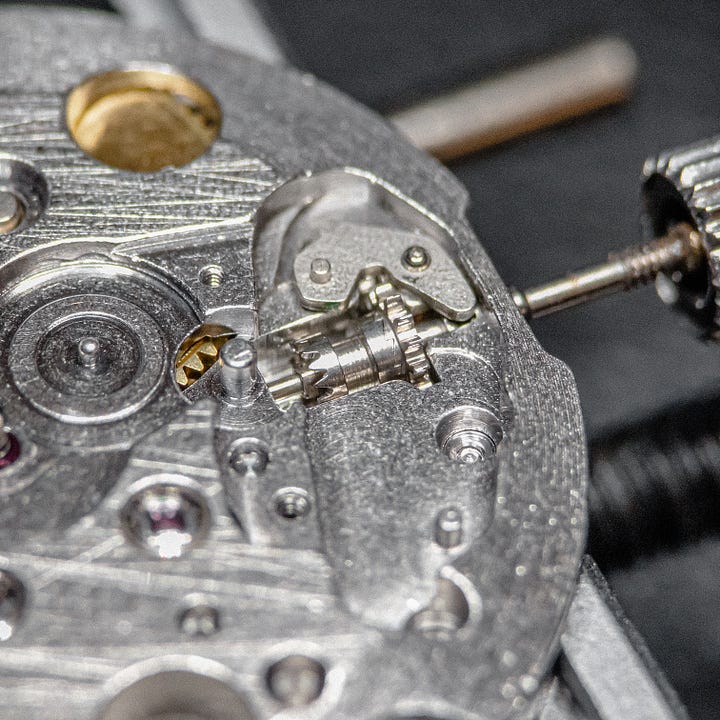

I really admire the construction of the setting lever mechanism in this movement. In my experience with Seiko, usually that part is accompanied by a screw that you loosen to release the stem, or by a detent post that lives between the mainplate and a balance-side bridge. Here however everything is held on by the setting lever spring, and as soon as that’s removed the setting lever and it’s post lift right out of their respective positions. It’s far less finicky to remove, and more importantly, reassemble. The yoke and its small jumpy spring come out no issue.

Bird’s eye view of the dial side disassembled before we turn our attention to the balance side.

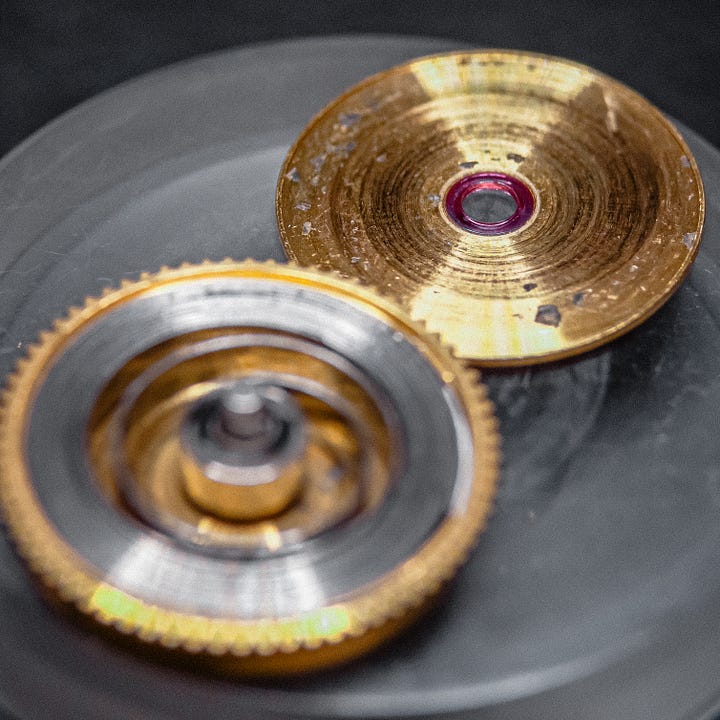

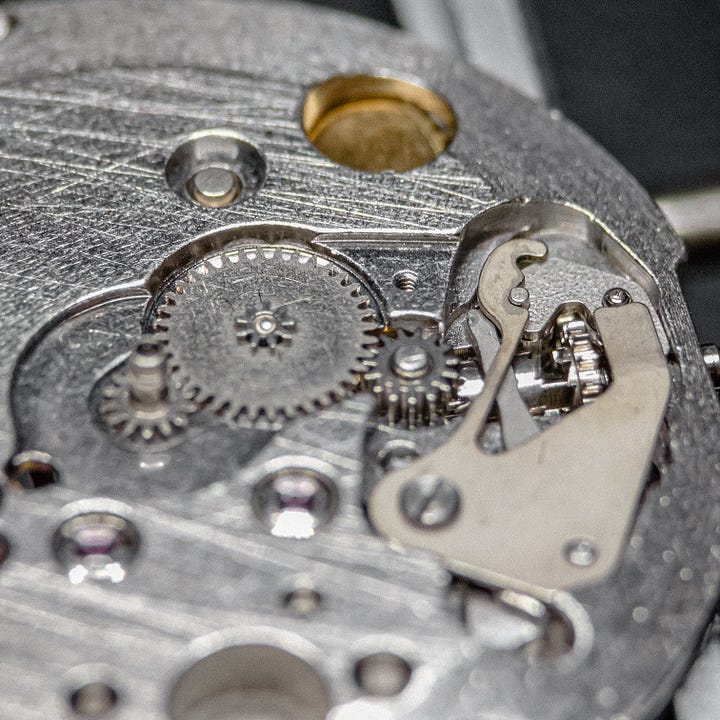

I tried as I disassembled the train side of the watch to document just. how. much. oil there was all over the movement. It shows up better in some photos than in others, but you can clearly see it all over the bottom side of the gear train bridge, smothering jewels, and somehow on the bottom side of the balance assembly. I hesitate to write ‘watchmaker’ as I look back at these photos, but the last person to put this watch back together had a real skill for finding inappropriate spots for oil.

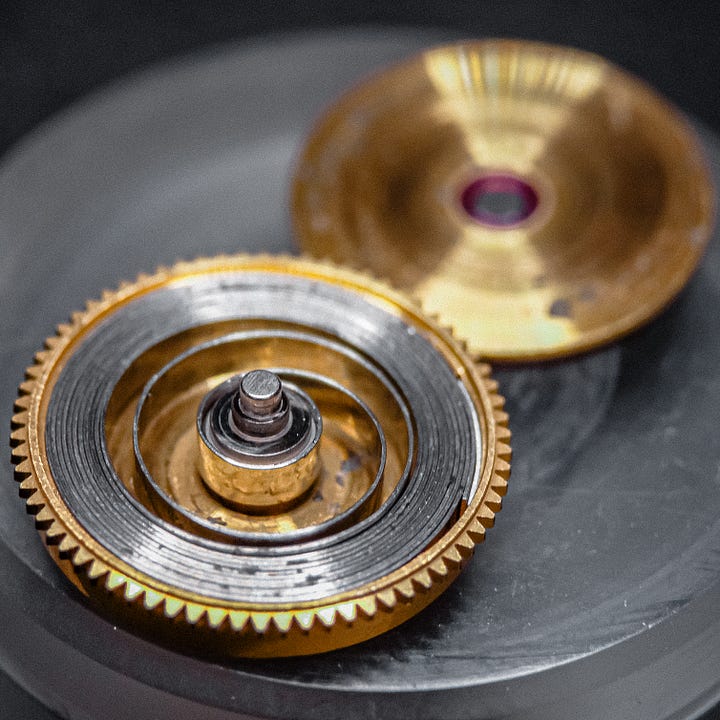

Everything taken apart without major event, I work the barrel open to find things in a pretty gross state. I’m hoping what I’m seeing is dried lubricant, but whatever it is isn’t pretty. Everything out of the barrel, I compare the existing mainspring (top) to its replacement (bottom). You can see how set the old one has become, all of its shape and spiral living up near the arbor. The new one has a nice shape that should encourage even power transmission through the entirety of the power reserve.

Note that the barrel cleaned up quite well, the jeweled lid ready to actually contribute to an acceptable amplitude with all of the crud caking the spring out of the way. Also of note the hairspring is in excellent shape, thank goodness.

Everything cleaned, and after applying the thinnest amount of grease that I could manage to my mainspring, into a winder and back into the barrel it went. I had to do some shaping at the arbor end to get the arbor hook to catch the tongue. I don’t love the shape it left near the arbor, but I’m hoping after some winding, unwinding, and settling it’ll smooth itself out. Lid on the barrel, the smallest amounts of HP-1300 I can muster where the arbor meets the barrel, and it’s ready for marriage to the mainplate.

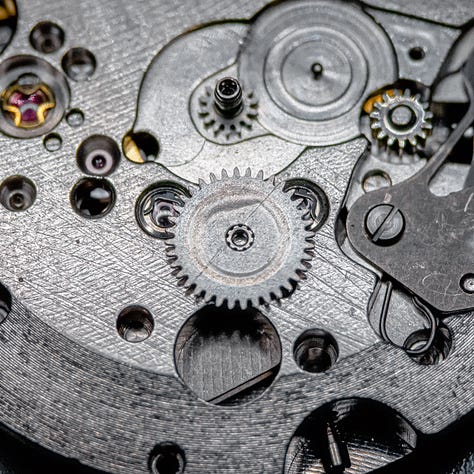

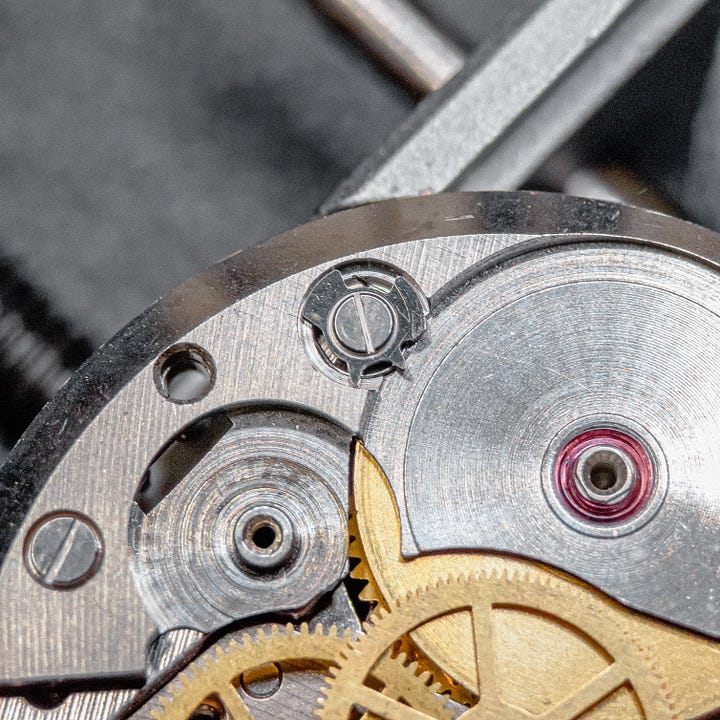

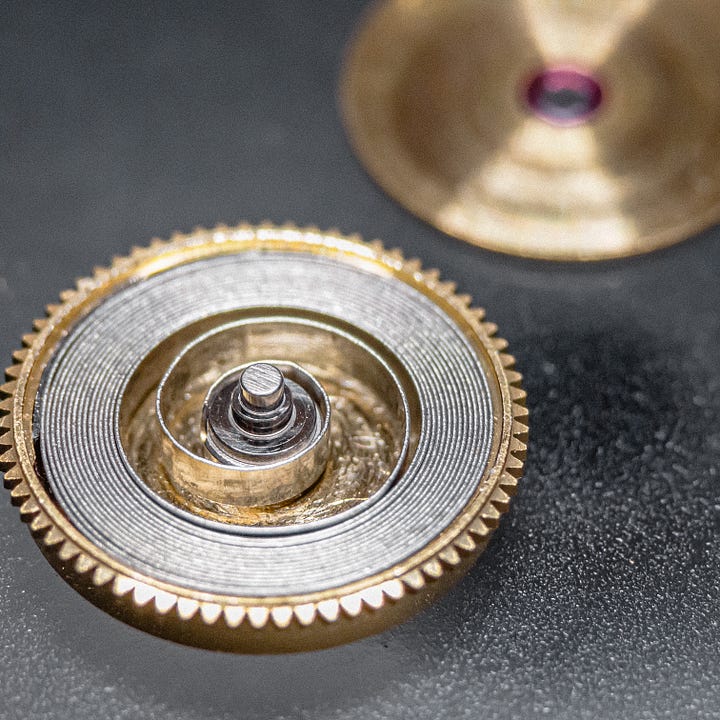

An element of this movement that I thought was really clever was this implementation of a separate holed jewel that is in its own setting and sits above the center wheel pivot. It’s meant for the shoulder of the fourth wheel sit on with the aim to separate the oiling of the center and fourth wheels. The center wheel turns once per hour, holding your minute hand, and is directly linked to the mainspring barrel, so it’s one of the highest areas of torque in the movement. Areas like this usually call for a pretty viscous lubricant like HP-1300, so it’s applied sparingly to the jewel you see the center wheel cylinder situated in. The fourth wheel, on the other hand, is separated from the center wheel in the gear train by the intermediate third wheel, turns once per minute, and usually holds your seconds hand. Due to the reduced torque and faster rotational speed of this wheel, usually a less viscous lubricant like 9010 is used, so it’s applied to the shoulder of the fourth wheel (not pictured). This specific jewel structure with one sitting above the other in a separate setting, allows different lubricants to be used without having to worry about them mixing on the same jewel.

Everything comes together well, the balance wheel kicks right up and everything’s running. I finish jewel lubrication up and I can let it run while I finish dial side.

I feel it a good moment to bring to your attention to how drastically lighting can change the perception of a watch’s condition. Above, the movement is photographed under my microscope light. Very minimal diffusion, a pretty close, harsh light source. For the purpose I need it to serve, it’s phenomenal. When I have a movement under my microscope I want to see its flaws, I need a light that will be revealing. If you compare that to the images below, however, you’ll see just how much even window light can clean up so many of the micro-abrasions on the metal in appearance. (The swirl on the ratchet wheel above is post-cleaning. I’m not sure if the swirling motion from a basket or another part colliding with the wheel in the basket was the cause, but it’s something I’ll be aware of moving forward in my process.)

I think this is important to note because I see dealers and buyers polarize both. Some buyers will shun a watch that has been intentionally photographed under harder light in order to emphasize flaws by an honest seller, and some sellers will use lighting tricks to photograph a watch far more beautifully than it will wear in most lighting conditions. It’s worth taking a moment to notice lighting quality in the photographs you’re shopping from or selling with, and let that aid in forming your view on a watch’s condition. Seeing a watch in multiple lighting conditions is the best way to view it if you can’t see it in person (and I would argue even when you can). If that isn’t possible, make note of what the intention of the seller seems to be with their photos, and sellers, clue your target audience in on your intentions behind your photos.

On the dial side, a quick progression through some reassembly with lubrication along the way.

Dial and hands back on. I always struggle with knowing whether to clean hands and indices, or to leave their wear. If there was something glaring like crud that could fall back into a movement, it would obviously be dealt with. Since that isn’t the case here though, and since this dial has a decent amount of visible wear, I conclude that perfectly pristine polish may look less at home here than on a dial in better condition. With their wear they remain.

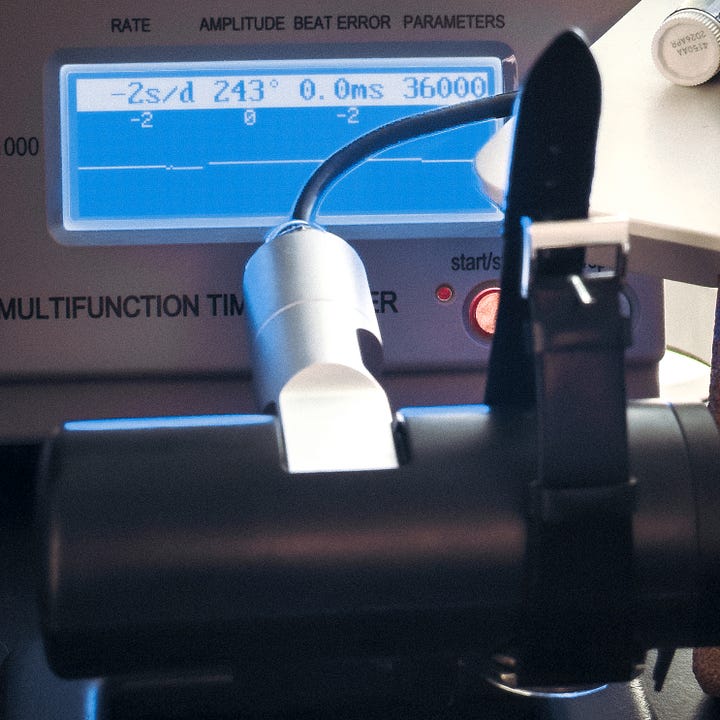

Movement cased and onto the timegrapher she goes. Readings aren’t horrible for immediately after service. Oils haven’t fully distributed, new mainspring needs a few full cycles to settle, but coming from our pre-service ~170 degrees, ~225-230 isn’t going to be a reading I turn my nose up at.

After about an hour I was consistently hitting 230 dial up and down, with only about a 5 degree drop in the vertical positions.

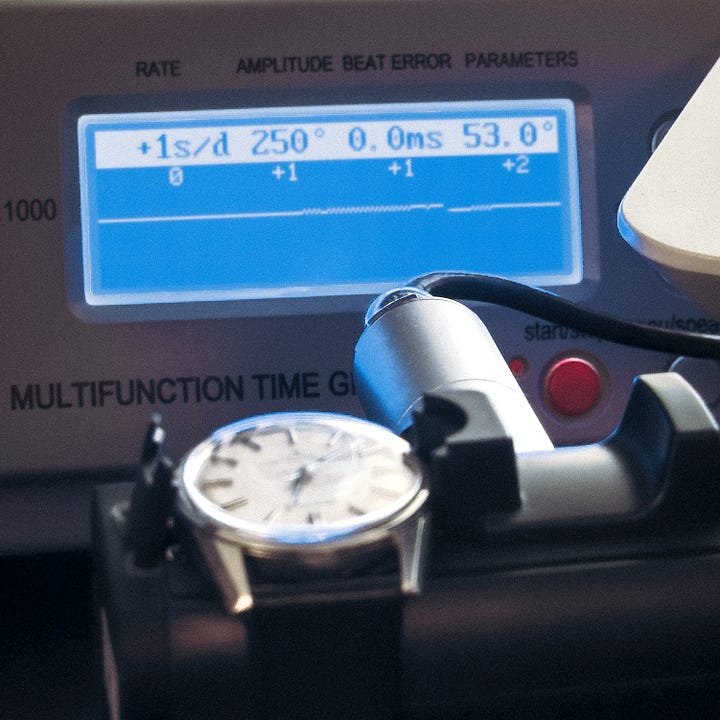

Below are some readings I took at the time of writing, about 2.5 weeks after service, hitting the mid 240s a few minutes after a full wind.

They aren’t ideal measurements, but they’re wearable measurements. For an almost 55 year old Seiko, I’ll give it (and more honestly, myself) some grace. Mainsprings are terribly difficult to source for this movement, especially in the U.S. right now, and I’m wondering if my limited choices play a part of my somewhat lethargic amplitude. (More on this in the footnote at the end.)

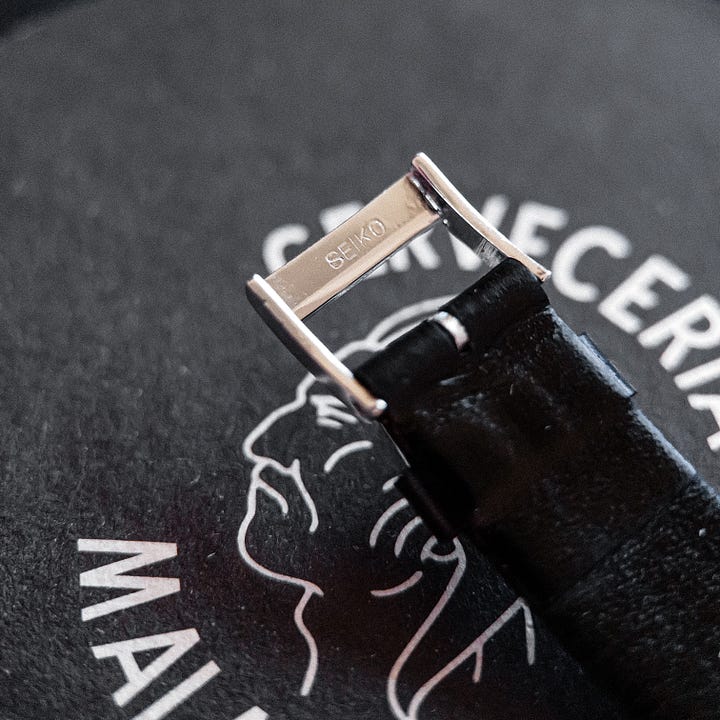

In all her glory. I managed to source an original seiko buckle from a strap that was falling apart. Replacing the 19mm-lug 14mm-buckle strap with something NOS vintage was a chore, but I found one.

Owen: the fast beating, still procurable, relatively well finished, mass produced, affordable, easily serviceable, reliable daily wearer makes a lot of sense sitting in its refreshed state on my wrist!

*I have sourced a new OEM caseback gasket, crown, and stem. With tarriffs, they’ll take a minute to make their way to my bench, but I will update when they’ve been situated in place.

And an addendum post service and writing, but a worthy mention for archival purposes:

As mentioned already, mainsprings for this watch are extremely difficult to get your hands on. For this service, I ordered a mainspring listed as compatible with the 5740C (which I later reckoned to be a GR4007D). After the service I found another 5740-8000, but with the applied arabic numeral indices for a similar steal of a price. Purchased and on it’s way, knowing it would need a service, I revisited the location I purchased the mainspring for the first 5740 from and they had already sold their remaining stock, which was a problem. Upon my initial investigation for these springs, that was the only place I’d found them available in the US. Time to do some investigating to see if I could find a spring marketed for another movement with the same specs. Down the EmmyWatch database rabbit hole, I found that the 5740C specifically uses Seiko mainspring part number 401431, while the lower beat A/B model predecessors used 401430. The specs for either aren’t readily available from Seiko, but looking at equivalents in GR lists I found the 401430 to be ~ 1.45 x .125 x 440 (or the same size as GR4007D).

Why then the spec change to 401431 for the C model? Best I can determine, geometry was changed throughout the movement to support the 36,000-beat speed of operation which means the barrel dimensions change, necessitating a shorter mainspring. I read stories of folks ordering a ‘5740 equivalent’ that claimed to work for the C model, then measuring them up against the springs removed from their 5740C barrels to find that the 5740C had a shorter spring, so the GR4007D that gets quoted all the time I knew wasn’t manufacturer spec (which means the mainspring currently in my watch isn’t correct lol). I measured the spring originally in my watch and it came in at much closer to 360mm than 440mm. I found one blog in Japanese that quoted a length ‘close to 30cm’, which somewhat aligned with my experience measuring my own original spring, but I assumed ‘close to 30cm’ was an approximation because 300mm would be an incredibly large delta from the power reserve in the A/B model to the C. Especially considering the increase in power a hi-beat movement would draw.

I’m not claiming my old one is original or even a replacement OEM Seiko part, but the presence of two different mainspring part numbers, seeing how much fuller my barrel was with the GR4007D than with the original spring, measuring my old spring, and reading from a third party that their spring measured well under 440mm had me skeptical about the GR equivalent everyone seemed to claim. After some confirmation that I was indeed looking for 1.45 x .125, I went on the hunt by size for a spring that would land under 400mm which I felt a good medium between what I knew of the lengths for 401430 and 401431. I found three 1.45 x .125 x 360 springs and bought them up, I wanted to have enough for my two, and an extra for the future with how difficult these seem to be to source.

Will update when new mainspring, crown, stem, and gasket are in and re-time.*

Update #1: New (correct) crown is on with its appropriate stem, decided to keep existing case gasket, still had plenty of elasticity. I did decide however to procure a different strap, the one from the photos above was glued, not stitched, which apparently doesn’t hold up well to leather conditioner after who knows how many years sitting in it’s original packaging. This one, also NOS vintage from the same company ‘Hadley Roma’, is stitched.